Highlights

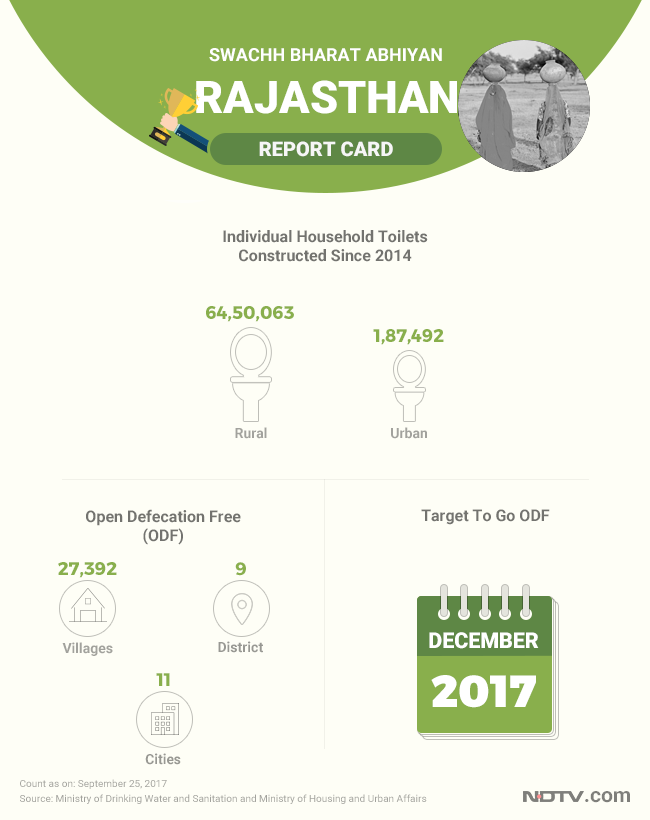

- Rajasthan’s sanitation coverage increased to 86.39% from 30.55% in 2014

- 11 out of 33 cities in Rajasthan are open defecation free

- Allegations of forcing to build toilets to meet targets have emerged

New Delhi: Kokila Damor, a 32-year-old resident of Dungarpur district in Rajasthan had known all her life that she could relieve herself either early in the morning or late at night. Those were the only two time slots possible to ensure that darkness would provide some sort of privacy and somewhat safeguard their dignity. Like millions of rural women across India, Kokila had no access to toilets nor the luxury to address nature’s call at any other time through the day. This routine, which she followed from her birth to marriage to motherhood changed in 2017 when she joined hundreds of women from her district to build 75,000 toilets in 100 days, ending the woes of open defecation permanently.

Success stories in improving rural sanitation are not new in Rajasthan. To give credit where its due, the state has been one of the top performers in the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and has embraced the sanitation mission from day one. The state has built over 60 lakh (64,50,063) individual household toilets (IHHLs) in its rural areas in three years, averaging nearly 20 lakh toilets per year, the highest among any Indian state. The state government has taken a special interest in sanitation and improved its rural sanitation coverage to 86.39 per cent from a low 30.55 per cent in 2014. The state’s interest in improving its sanitation was visible from the fact that for the financial year 2016-17, Rajasthan spent 99 per cent of its allocated budget of 634 crores in construction of IHHLs in rural areas.

Improving rural sanitation has been our priority ever since we launched the mission. The sanitation scenario in rural Rajasthan was very poor, and awareness among people was really low. People used to think that constructing toilets was a costly affair and did not want to invest in it as they were also concerned about their maintenance. Local administrations and NGOs went from door-to-door to explain people about the importance of having toilets and people caught on soon enough, said Dr Ayushi Ajey Malik, Director, Swachh Bharat (Gramin), Rajasthan.

But so far the state has only nine open defecation free (ODF) districts out of a total 33. Rajasthan’s improvement in rural sanitation, is not without its share of controversies. The trouble began when the Panchayati Raj department could confirm only 18 lakh completed toilets, as per photographs uploaded by local administrations. Recent allegations emerging out from some sources state that some local administrations, in their bid to meet the October 2019 ODF deadline (for rural Rajasthan) are coercing villagers into building toilets. These coercion include denial of subsidised rations and denial of work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). Though no direct orders have come from the state government, villagers have alleged that local administrations have themselves decided to impose such restrictions to force villagers into building toilets, despite their complaints of not being able to afford them. Water is another problem in Rajasthan, as several rural households still do not get access to regular tapped water and building toilets, without solving the problem of water, imposes an additional burden on them.

The importance of sanitation is undeniable but that should come with awareness and proper supply of toilet building materials for people who do not have toilets in their homes. Arresting people or denying them ration will not serve the purpose of the Swachh Bharat Mission as people will then build toilets out of fear and not out of understanding the importance of sanitation, which can impact the campaign’s long term goals, said Ajay Sharma, Member of Rajasthan Gramin Vikas Sangathan, an NGO working for rural development in the state.

Initially we would only tell the villagers about such restrictions, that too only in villages where construction activities had come to a standstill. But the situation has now taken a bad turn as many districts and blocks are actually imposing restrictions on ration and daily work if toilets are not built. This is unfortunate, said an official from Jhalawar District Administration.

On the urban front, Rajasthan has done well in terms of improving sanitation conditions. 11 out of the state’s 33 cities have become ODF and the rest are slated to attain the ODF status by the end of 2017. The number of IHHLs constructed across the state stand at over 1.8 lakh (1,87,492), highest among northern Indian states. Over 2,000 public and community seats have also been placed across cities and towns in Rajasthan. Maintenance of public toilets however, is a key issue in urban Rajasthan and is still not implemented with precision. The poor ranking of major cities Jodhpur (209), Jaipur (215) and Udaipur (310) in Swachh Survekshan 2017, second the ill-maintenance of public toilets in urban Rajasthan.

In the past three years what Rajasthan has truly achieved is a sense of change among its people who for decades had lived in conditions where toilets remained a luxury. Dungarpur stands out as a striking example where women from several villages, breaking class and caste barriers came together to end their decades old woes of open defecation. On the occasion of Raksha Bandhan this year, 1,000 brothers from the village of Bhalo ka Gurha in Udaipur helped build toilets for their sisters. In Kota, the district administration introduced two types of stamps – Kanchan (for houses with toilets) and Shochalaya Vihin (for houses without toilets). The stamps have been placed in textbooks and distributed across more than 1,300 schools. The alleged coercion, however, remain a matter of concern as in the long run, coercion does not go well with the objective of behavioural change that is a must to ensure that toilets built are actually used.